Hospitals and health systems face constant pressure to balance innovation with financial stewardship. Relying on the right revenue cycle management partner to pilot and validate emerging technologies allows hospitals to sidestep the high costs, operational risks and distraction of building in-house “start-up” capabilities.

An end-to-end RCM partner like Ensemble brings specialized expertise, proven frameworks and the ability to absorb early-stage errors, so hospitals don’t have to invest in expensive infrastructure or retraining. This approach protects capital and reduces the risk of unsustainable expenses while keeping the organization’s focus on delivering high-quality clinical care.

But what are the tools that are being assessed?

Every technology shift in the healthcare industry creates a temptation to apply the new tool to every problem. That’s what we’re seeing with large language models (LLMs) today. The truth is, not every workflow benefits from a model that “reasons.” Some problems need prediction; others need precision. Some need exploration; others need control.

Understanding when to use an open reasoning model versus a deterministic or predictive system is the new systems-thinking challenge. Let’s break that down.

The three lenses: effectiveness, efficiency and cost

Lens

Effectiveness

Efficiency

Cost

Core Question

Does it improve the outcome quality?

Does it reduce cycle time or human effort?

Does it justify the compute, integration and error cost?

Example Metric

Accuracy, recall, relevance

Task completion time, agent handoff rate

Cost per 1K tokens, rework time, supervision hours

If it’s high-value but low-tolerance for error (like financial reconciliation), deterministic systems win. If it’s ambiguous, language-based or multi-factorial (like summarizing clinical notes or writing appeals), reasoning models add value. If it’s highly repetitive, rule-bound and measurable (like claim edits), predictive or deterministic systems outperform reasoning models on cost and reliability.

The framework: "R.E.A.L."

Step

R — Reasoning needed?

E — Error tolerance defined?

A — Available data type?

L — Latency vs. learning tradeoff

Description

Does the problem require contextual synthesis, judgment, or multi-variable reasoning?

How much error can the system absorb before cost or compliance risk outweighs speed?

Do you have structured, labeled data or mostly unstructured narratives?

Is it more important to get to an output quickly or to improve over time?

Example

Interpreting denial letters or coding documentation.

Appeals generation can tolerate 10% edits; payment posting cannot.

Eligibility checks use structured data; prior auth notes do not.

A chatbot can iterate; a claims router must decide instantly.

If three of the four lean toward “Reasoning / Context,” use an LLM or open reasoning model. If three lean toward “Control / Determinism,” stay with algorithmic or predictive logic.

Practical use cases in revenue cycle management

Revenue cycle example: Denial prevention vs. Denial appeals

Denial prevention: Rules-based, deterministic systems are optimal. You know the payer rules, and you can code deterministic edits. Adding a reasoning model increases cost and potential drift without clear benefit. However, you can use reasoning models to explore large datasets and look for potential new rules. You can also use machine learning classification models such as regression, random forest or gradient boosting if the rule set is not easily written as “If X then Y”. These models are still much more efficient than broad-based LLM models.

Denial appeals: Context matters — clinical justification, payer policy and tone. An LLM with reasoning and retrieval capabilities can draft appeal letters 3–4x faster than humans, with a small manual review loop.

Ensemble’s data shows 40%–60% cycle time reduction for appeal generation using Generative AI.

Cost and control: The hidden variables

Model Type

Deterministic

Predictive

Reasoning (LLM)

Unit Cost

Low

Medium

High

Error Cost

Low

Medium

Variable

Control Level

High

Medium

Low-Medium

Ideal Use Case

Compliance, validation, automation at scale

Forecasting, triage, prioritization

Interpretation, communication, synthesis

When evaluating AI in revenue cycle, the total cost equation matters — not just model performance. That equation should include compute, supervision time, correction rework, regulatory or reputational risk and the costs of model retraining or context injection. For example, running GPT‑4 Turbo on 10 million claims would exceed $1 million per month in token cost alone, while deterministic logic could accomplish the same work for <$10K. Overlooking hidden costs like this can turn a promising AI initiative into an unsustainable expense, eroding ROI and slowing adoption.

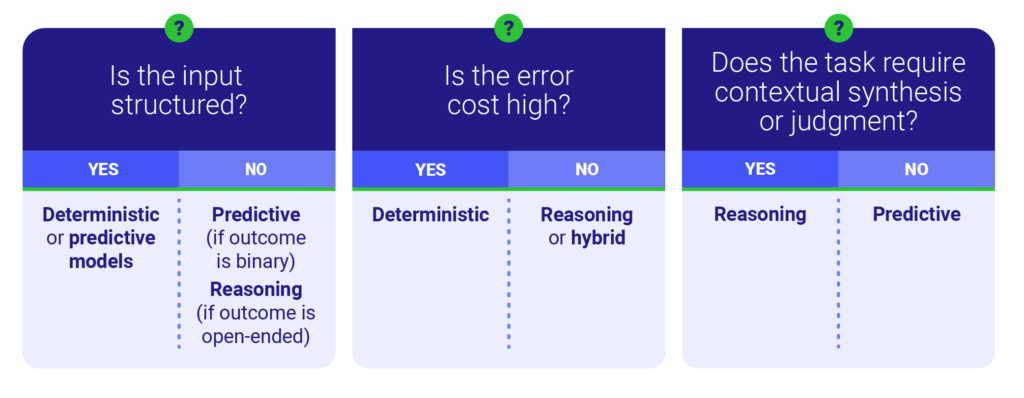

The decision tree

If the input is structured, use deterministic or predictive models. If it is not, the next question is whether the outcome is binary or open-ended. If binary, use predictive models. If open-ended, use reasoning models. If the error cost is high, a deterministic model is a good fit. If not, use reasoning or hybrid models. Finally, consider if the task requires contextual synthesis or judgment. If yes, use a reasoning model. If not, choose a predictive model.

Bringing it together: Hybrid systems win

The best architectures combine reasoning, predictive and deterministic logic — not as competing models, but as layers of trust and speed.

- Layer 1: Deterministic filters — data validation, policy edits.

- Layer 2: Predictive triage — probability of denial, next-best action.

- Layer 3: Reasoning model — narrative generation, summarization, contextual insight.

Each layer narrows the field, improving both efficiency and controllability. You get the speed of automation without the chaos of unbounded reasoning.

The goal isn’t to use LLMs everywhere — it’s to use them where human reasoning is the bottleneck. And remember: if you can define the outcome with a clear rule, code it. If you can’t, predict it. If you still can’t, reason it.